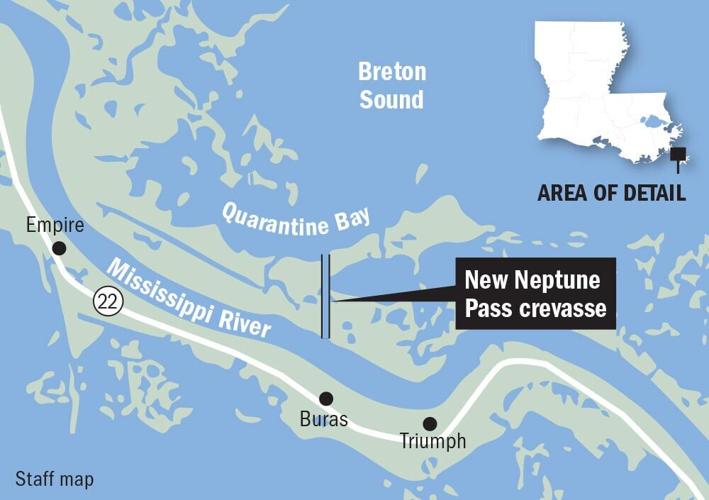

A mammoth break in the Mississippi River’s banks far south of New Orleans is building substantial amounts of new land in a heavily eroded part of the coast, a new study finds, adding to the debate over whether and how it should be plugged.

The break, known as Neptune Pass, has grown so large it is comparable to the 10th-largest river in North America and the 100th-largest in the world, the new study by coastal scientist Alex Kolker and his collaborators finds.

That has posed hazards for shipping, but it is also acting as a natural river diversion, delivering sediment into a nearby bay in Breton Sound on the river’s east bank. For that reason, it has formed part of the debate over controversial efforts to build large-scale, man-made river diversions under the state’s coastal restoration plans.

There has been uncertainty over whether the land being built by Neptune Pass, amounting to several thousand acres, is primarily because of sediment that the river’s current is scouring from the pass' banks and moving farther back, or if it is the result of new sediment traveling down the Mississippi.

Kolker and his team set out to answer that question — key in part because land being built with new sediment would indicate the potential for man-made diversions to help restore Louisiana’s coast. Such diversions seek to mimic how south Louisiana was formed thousands of years ago, when the river ran free, depositing sediment along the way.

Almost like walking on water. A tour group is able to stand in Quarantine Bay thanks to a new natural diversion from the Mississippi River delivering fresh sediment to the east side of the river across from Buras on Monday, September 12, 2022. Just two years ago this wouldn't have been possible as the water was too deep. (Photo by Chris Granger | The Times-Picayune | The New Orleans Advocate)

The study published in the peer-reviewed scientific journal PLOS One found that the land being built in nearby Quarantine Bay was 56%-79% larger than the amount of sediment scoured from the pass itself. That indicates a large portion of the new delta is being constructed with sediment from the river.

The work was done using a combination of sediment sampling, drone surveys and satellite images, among other tools.

“The big takeaway is that it is building land in Louisiana,” Kolker, a scientist with the Louisiana Universities Marine Consortium, said in an interview. “It is building a delta that is new land.”

Compromise plan

The findings are timely. The Army Corps of Engineers has been working on a plan to partially plug the pass, reducing its flow to what it was before the extraordinarily high river of 2019 blew it out to its current state.

Before that, it had been a small channel about 150 feet wide, located below where the river levees end. Its width quadrupled and its depth increased around five times over, reaching up to about 100 feet. The pass now regularly steals around 15% of the river’s flow, Kolker’s team found.

That has slowed the river’s currents, allowing sediment to drop to the bottom earlier than it would. The Corps has had to dredge in spots it never had to before to keep the path clear for shipping vessels as a result.

The strong pull on the river’s current has also posed a hazard for vessels traversing one of the world’s most important shipping lanes, forcing the Corps to construct a temporary fix, installing a blanket of stone to stabilize the banks.

Separately, there have also been indications that the pass is helping worsen saltwater intrusion up the river because of the weakened current in the main channel.

The plan the Corps is pursuing is a hybrid, seeking to deal with those problems but still allowing the pass to build land behind it by incorporating coastal restoration techniques.

It includes a rock sill at the entrance with a notch in the middle to allow recreational boats, water and sediment to pass through. V-shaped structures known as sediment retention enhancement devices, or SREDs, made with mud, fabric and stone, would be built in Quarantine Bay, where the pass leads.

Those terrace-like devices would, in theory, slow the flow of water and allow sediment to be deposited.

The Corps released a report Thursday concluding the plan would not significantly impact the environment, and construction is expected to begin by early summer. The full cost is still being determined, but initial work on the rock structure near the bankline has been estimated at up to $20 million, said Corps spokesman Ricky Boyett.

'Largest system of its kind'

Coastal advocacy groups have lauded the Corps’ willingness to think creatively on a compromise rather than simply close the pass. Those groups, as well as Kolker, stress that they understand the concerns regarding shipping and would not want to see hazardous conditions persist.

Kolker also welcomed the compromise plan, though he said he had some concerns over how the terrace-like structures would be built and their effectiveness. He hoped some of his questions on those details could be answered.

As for the larger debate on diversions, that is unlikely to be settled anytime soon. Gov. Jeff Landry’s administration has indicated it intends to cancel plans for the $3 billion Mid-Barataria Sediment Diversion on the river’s west bank, mostly paid for with money related to the 2010 BP oil spill. He is opposed largely due to the drastic effects it will have on commercial fishing for oyster and shrimp in the diversion area, forcing fishers to move or find new work.

Two years ago this was open water, but now, thanks to a new natural diversion from the Mississippi River that delivers fresh sediment, grasses can grow which help lay the foundation for wetland restoration and land building. (Photo by Chris Granger | The Times-Picayune | The New Orleans Advocate)

A similar diversion, though somewhat smaller, had been planned for the river’s east bank. It is unclear whether those plans will move ahead, but Landry’s opposition to Mid-Barataria raises serious questions over its fate.

Still, Neptune Pass’ developments will continue to hold lessons for Louisiana and far beyond.

As Kolker’s paper notes: “These findings provide key insights that are critical to the restoration and safe management of the Mississippi River and its delta, the largest system of its kind in North America.”

This story was corrected to clarify that a large portion of the new delta is being constructed with sediment from the river. It is not clear whether river sediment is responsible for most of it.